Extreme heat is the deadliest weather-related hazard in the United States. Washington summers are getting longer and hotter, and extreme heat waves are becoming more frequent. But the impacts of extreme heat are not evenly distributed. Location matters. Some communities and families are impacted by excessive heat more than others, and this can worsen health inequities.

People who live in historically disinvested neighborhoods, who have limited access to resources and greenspace, and those struggling with additional health issues are all at greater risk for impacts from extreme heat.

The Clark County Heat Watch provides a snapshot in time of how urban heat varies across neighborhoods in the county and how local landscape features affect temperature and humidity. This data can be used to inform community decision-making, guide plans to mitigate the impact of hotter summers, create more resilient communities and save lives.

Results

Cities and more developed areas tend to be warmer than surrounding rural or less developed areas. These areas are referred to as urban heat islands. Buildings, roads, and other paved surfaces with a lack of shade hold on to more heat than natural landscapes or areas with more trees.

- In Clark County, areas with more buildings and development tend to be hotter during the afternoon. Industrial land use appears to create pockets of higher heat near residential areas.

- The hottest areas in the afternoon were most of the Vancouver area, including downtown, Orchards, Fourth Plain, and Fruit Valley. Washougal, downtown Camas, and downtown Battle Ground also had areas with higher temperatures.

- Cooler places during the afternoon included west and central Camas, and places with more green and natural spaces, like Burnt Bridge Creek Trail area in Vancouver. Areas with parks and street trees can provide relief from heat in denser urban areas.

- There is nearly a 10-degree difference in temperature during the evening, depending on location. In the evening, hotter areas included Washougal, central and east Vancouver (especially Ogden, Bennington, and Fisher’s Landing East neighborhoods).

- Ridgefield, La Center, northwestern Vancouver (Mount Vista, Felida, and Lake Shore neighborhoods), and northwest Battle Ground (Cherry Grove) appeared cooler in the evening.

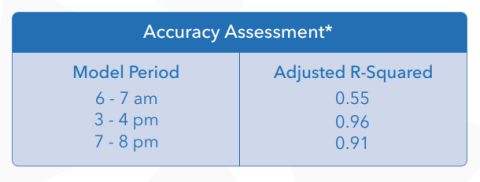

- General limitations: Heat data was collected on one day in July 2024. We recommend data users focus more on the pattern of temperatures (hotter or cooler places) within each period, versus the actual temperatures measured at one point in time.

How this data will be used

Clark County Public Health plans to compare Heat Watch data with other maps that include information about the built environment, social factors, and health inequities to further identify opportunities to support local communities with heat adaptation and resiliency efforts.

How communities, organizations, and decision-makers can use this data

Heat maps can be used to inform the development and implementation of a range of cooling activities through land use, built environment, transportation, and community infrastructure policies and plans. The data can also be used to support grant applications, the development of extreme heat preparedness and response plans, and long-term climate action strategies.

Use this data when:

- Determining where to plant trees and increase vegetation/green spaces.

- Planning and designing infrastructure to include green roofs, green stormwater, and smart surface updates.

- Prioritizing where to add temporary or permanent shelters (e.g., cooling centers and covered bus stops).

- Advocating to preserve existing natural areas that provide respite from heat.

- Prioritizing equitable planning, collaboration and community engagement.

- Applying for energy-efficient upgrades and retrofits incentives (e.g., replacing oil and gas-based systems with heat pumps).

Additional resources

- Environmental Protection Agency Heat Island Community Actions database

- Healthy Community Design and Climate

- National Integrated Heat Health Information System's Mapping Campaign

- Washington Department of Health Take Action to Reduce the Severity of Climate Change

- Washington Department of Health What You Can Do - Climate Change